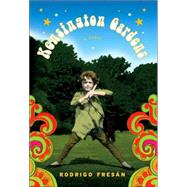

Kensington Gardens; A Novel

by Rodrigo Fresán; Translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer-

This Item Qualifies for Free Shipping!*

*Excludes marketplace orders.

Rent Book

New Book

We're Sorry

Sold Out

Used Book

We're Sorry

Sold Out

eBook

We're Sorry

Not Available

How Marketplace Works:

- This item is offered by an independent seller and not shipped from our warehouse

- Item details like edition and cover design may differ from our description; see seller's comments before ordering.

- Sellers much confirm and ship within two business days; otherwise, the order will be cancelled and refunded.

- Marketplace purchases cannot be returned to eCampus.com. Contact the seller directly for inquiries; if no response within two days, contact customer service.

- Additional shipping costs apply to Marketplace purchases. Review shipping costs at checkout.

Summary

Author Biography

Excerpts

THE CONDEMNED

It begins with a boy who was never a man and ends with a man who was never a boy.

Something like that.

Or better: it begins with a man’s suicide and a boy’s death, and ends with a boy’s death and a man’s suicide.

Or with various deaths and various suicides at varying ages.

I’m not sure. It doesn’t matter.

Everybody knows—it’s understandable, excusable—that numbers, names, and faces are the first to be jettisoned or to throw themselves from the platform during the shipwreck of memory, which always lies there ready for annihilation on the rails of the past.

One thing, at any rate, is clear. At the end of the beginning—at the beginning of the end—Peter Pan dies.

Peter Pan kills himself and here comes the train. The scream of steel hurtling through the guts of London like a curse, like the happiest of lost souls.

Peter Pan jumps onto the tracks at just the right moment. Peter Pan is one of those two people a week who—statistics say—throw themselves onto the rails with British punctuality just before the train’s triumphal entrance.

A woman screams when she sees him jump. A woman screams when she sees a woman screaming. All at once—screams are more contagious than laughter, and there are so many screams in this story—it’s the same scream that leaps from woman to woman, from mouth to mouth. The same scream makes the cars brake, and the brakes also scream at the unexpected and futile effort of having to stop all those wheels and all the steel riding on those wheels. Yes, without warning the whole world is one single scream.

It’s April 5, 1960, the hypothetical day of my increasingly hypothetical birth (the scream of my hypothetical mother, who spreads her legs to push me and my hypothetical first scream out), and it’s the day of the death and suicide of the respected publisher Peter Llewelyn Davies, founder of Peter Davies Ltd., considered an “artist among editors.”

“Peter Pan Becomes a Publisher,” ran the headline reporting the professional birth of the man who now emerges at dusk from the Royal Court Hotel and crosses Sloane Square, thinking that he became an editor in an attempt to vanquish the horror of having been a character for so many years, too many years. And I like to think—because it’s so fitting at the start of a book, and because certain gestures tell us so much about a protagonist—that Peter Llewelyn Davies is accosted by an anachronistic pack of Chelsea beggar boys; I hesitate when it comes to deciding whether he passes out a handful of coins. What I am sure of is that Peter Llewelyn Davies goes down the stairs to the underground station and waits a few minutes on the platform, until he sees the light at the end of the tunnel, a light that grows steadily stronger and closer. Peter Llewelyn Davies jumps and doesn’t scream. Let everybody else scream, thinks Peter Llewelyn Davies, in the enormous second it takes his body to fall to the rails; then comes a blue spark, and a smell of electricity, and the wheels, and the scream, and the screams.

To believe—if karma’s concentric spirals and the zigzagging laws of reincarnation don’t deem it impossible—that the immortal spirit of Peter Llewelyn Davies abandons his ruined body and floats far away, and then enters my brand-new self at almost the instant I am born, is immensely tempting. If that’s how it was and always had been, my story would be so clear, so easy to understand, that it would no longer be necessary to leave all the windows open or closed each night, waiting for some act of redemption or punishment to justify the course of my life.

But sorry—nothing is that simple. Certain explanations are pertinent, inevitable.

Certain explanations take time.

Others are quicker: Peter Llewelyn Davies is the real name of Peter Pan, or Peter Pan is the real name of Peter Llewelyn Davies. It doesn’t matter who’s the shadow of whom, or whose shadow is sewn to the other’s heels. What matters now are the cars full of people on their way home; the screams and the scream bouncing off the tile of the underground walls; the oxygen breathed too many times down there in the eternal concave dusk of train stations.

There was a time, thinks Peter Llewelyn Davies, when we came down into these depths not to die but to keep from dying. The long, tribal, brightly lit nights of the Second World War, of the War Even Greater than the Great War. The word war brings Peter Llewelyn Davies bad memories, takes him back to his war, to the trenches of the Somme.

So Peter Llewelyn Davies makes an effort and remembers the other war, the war that came after his. The war that he didn’t fight in, but that reached him anyway, because wars always manage to find you wherever you are. Everybody together down here in the underground stations turned into shelters singing Vera Lynn’s “We’ll Meet Again” at the top of their lungs to drown out the sound of the sirens and the shudders of the Blitz. Everybody together reading magazines by torch, magazines with some cartoonist’s sketch of Hitler as Captain Hook, his hook raised. Everybody drinking tea, nearly transparent and hardly tasting of tea, like members of a secret society, like the first Christians, like prehistoric shamans telling stories and painting them on the walls. Everybody together experiencing the queer contradiction of burying themselves in order to be closer to God, to heaven. Yes, for once heaven was underground and hell was the skies where the Luftwaffe flew, and beyond—much higher and farther, second star to the right, and straight on till morning—was Neverland.

Peter Llewelyn Davies looks up and looks down and grips his furled umbrella and light briefcase so as not to go flying off, swept away by the wind of his past towards that faraway island inhabited by pirates and crocodiles and the terrible promise of eternal irresponsible childhood. That’s how Peter Llewelyn Davies feels: light, like a ghost of himself; like a reversed X-ray, bones on the outside; as if he’s gone back in time and is running in Kensington Gardens again; like a story worn out after having been told too many times, whose only salvation is this unexpected ending—real, undeniably true.

Excerpted from Kensington Gardens by Rodrigo Fresan

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.

An electronic version of this book is available through VitalSource.

This book is viewable on PC, Mac, iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch, and most smartphones.

By purchasing, you will be able to view this book online, as well as download it, for the chosen number of days.

Digital License

You are licensing a digital product for a set duration. Durations are set forth in the product description, with "Lifetime" typically meaning five (5) years of online access and permanent download to a supported device. All licenses are non-transferable.

More details can be found here.

A downloadable version of this book is available through the eCampus Reader or compatible Adobe readers.

Applications are available on iOS, Android, PC, Mac, and Windows Mobile platforms.

Please view the compatibility matrix prior to purchase.